Love and War: Digitized Letters Preserve the Tale of a Texas Girl, Her Confederate Sweetheart and their Secret Engagement

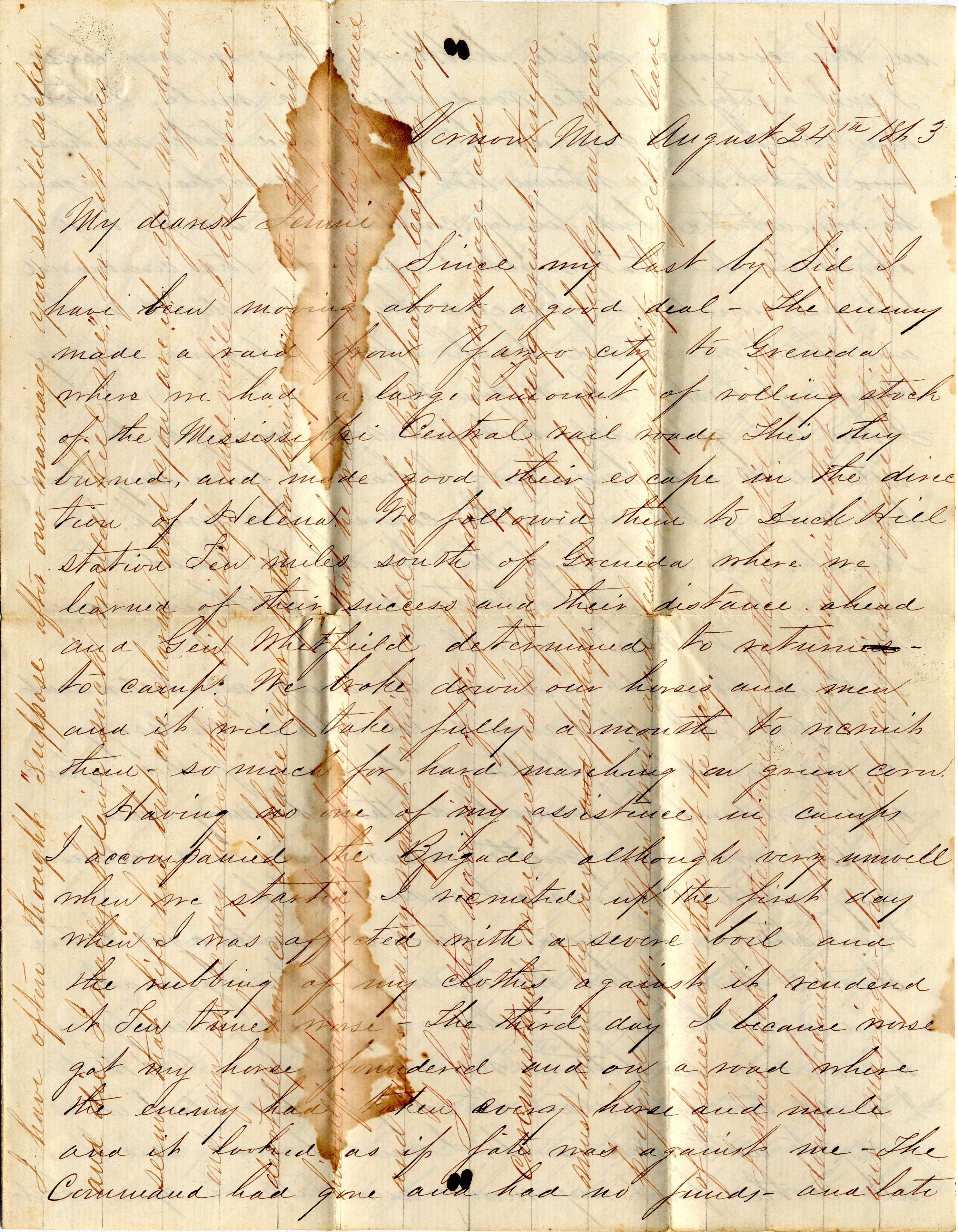

Civil War letter from Maj. John Coleman to fiance Jennie Adkins (Photo courtesy of The Texas Collection via Baylor University Digital Collection)

'This is the raw stuff of history,' curator says of the writings in The Texas Collection at Baylor University

Follow us on Twitter:@BaylorUMedia

Contact: Terry Goodrich,(254) 710-3321

WACO, Texas (Feb. 10, 2017) — Feb. 14 was coming up quickly, and the two young lovers' emotions were heating up the hundreds of miles between them.

The 16-year-old girl wrote to her adored fiancé that "my heart is ever with you, my prayers daily offered up for you."

The young Confederate soldier rhapsodized about his "darling angel" and his desire to "plant a lover's kiss on thy ruby lips and with words of burning love rekindle the fire of devotion ... "

They were secretly engaged, and they sent their love, not with a tap of a finger on a cellphone, but by pressing quill pen to paper in letters that today — more than 150 years after the Civil War that kept them apart — are creased, torn and turned rusty in places.

They wrote at least 32 letters to one another between 1861 and 1864, often waiting a month or two to receive them because of slow and unreliable wartime mail. While some bear February 1863 dates, not one mentions Valentine's Day — unusual compared with modern times, says Eric Ames, digital collections curator for Baylor University Libraries.

Feb. 14 as a romantic holiday was still relatively new in the United States. Or "it may just be that then, it wasn't a matter of, 'This is a special day to tell you how much I love you,'" Ames said. "If you were thinking, 'I could die any day,' then you took any day, every chance you got, to say, 'I love you.'"

Ames scanned, transcribed and uploaded the letters of Virginia Eliza "Jennie" Adkins — the daughter of a Marshall, Texas, judge — and Maj. John Nathan Coleman, commissary officer of the Third Texas Cavalry, which saw action at such key battles as the one at Pea Ridge, Arkansas, the siege of Vicksburg, Mississippi, and the Atlanta campaign. The digitized letters are housed in The Texas Collection at Baylor.

While Coleman was responsible for procurement of food and other supplies, he saw "a fair amount of combat," Ames said. But he spared his wife-to-be the violent details — "TMI," by today's social media standards — in his letters.

"Even in the darkest days of our confederacy I tried to cheer you up," he wrote.

Just as social media today carries the risk of misinterpretation, so did the couple's written correspondence. As they waited for the next letter, both had ample time to read between the lines for implications, both good and bad.

Coleman, who was 26 when the war began, was "a pretty typical jealous boyfriend" — troubled to learn about the concerts and balls that Adkins occasionally attended with some officers stationed in Marshall, Ames said.

Adkins assured him, "You cannot conceive how much you are loved, and how often you are thought of."

Sometimes the soldier's life was monotonous, sometimes filled with dread and sorrow — and nearly always uncomfortable, despite the socks and comforter that Adkins sent him.

"I . . . can sleep in a mud hole as comfortable as a feather bed," he wrote. Occasionally, there was respite — such as meeting kind people in Tennessee and enjoying maple syrup and molasses there.

"It is a new thing to us to see the trees dripping" sap, Coleman wrote.

On a somber note, Adkins wrote that one Christmas, while attending parties, "I often thought I could hear you calling me by my name . . . I left one night from a party before I had been there an hour. All at once a feeling came over me I could not account for . . . Don't think I was the least superstitious, but after referring to your letters, I find that about that time you were in a battle . . . "

As the war continued, paper became scarce and expensive. At times, the youthful pair's intense back-and-forthing was "a little schizophrenic, and he (Coleman) gets melodramatic as he realizes there is no way the South will win," Ames said. "He just wants to get back."

Sometimes, a jest was mistaken for a jab, and apologies ensued. And then there is the puzzle of Coleman's hair.

"My health is better than in two years . . . even my baldness is passing away and a beautiful black hair is once more covering my head," Coleman wrote. "My whiskers have also returned much blacker and have grown four inches long."

Responded Adkins: "I am very happy to know you are enjoying good health, and that your hair is growing out thick and black. After all I will not have a gray baldheaded husband. But I don't like very long whiskers."

Ames said the discussion "struck me as joking. But that's always the challenge with these kinds of letters. They never had any reason to think anyone else would ever read these letters."

How did the two meet? What sparked the flame? And most of all, why did they keep their engagement secret?

Some letters imply that Adkins' father would have disapproved, perhaps questioning Coleman's social standing or financial status. But "that's just a guess," Ames said.

Coleman, a merchant who owned a business before the war, had "a spotless military record" by war's end, Ames said.

"There's more to this story," he said. "There are some letters we know are missing that were mentioned in others.

"I wish we had a little more to fill the gaps. But the letters do paint a pretty clear story of how they felt about each other and the deprivations of war. This is the raw stuff of history."

Ames' research revealed that Coleman survived — as did the couple's love. They were married in August 1865, when Coleman returned to Marshall after receiving a parole from the Union Army, and they had six children. Coleman lost both legs in an industrial accident, and, in 1880, died at age 45. His wife never remarried, receiving a Confederate widower's pension from the state of Texas for the final 18 years of her life. She died in 1932 at age 87.

*The letters were loaned to Baylor by the late Dr. Douglas Guthrie, a Mexia podiatrist and Civil War buff. He learned from a patient -- a great-granddaughter of Jennie Adkins -- that she and some relatives had dozens of letters written by a Confederate officer and his fiancée, and she offered to give her share of the letters to him. Guthrie attended a lecture by John Wilson, director of The Texas Collection, and after speaking with Wilson, agreed to loan the letters to Baylor. The digitized letters are in an online database in The Texas Collection in Carroll Library, 1429 S. Fifth St. on campus and may be viewed by appointment. For more information, call (254) 710-1268.

ABOUT BAYLOR UNIVERSITY

Baylor University is a private Christian University and a nationally ranked research institution. The University provides a vibrant campus community for more than 16,000 students by blending interdisciplinary research with an international reputation for educational excellence and a faculty commitment to teaching and scholarship. Chartered in 1845 by the Republic of Texas through the efforts of Baptist pioneers, Baylor is the oldest continually operating University in Texas. Located in Waco, Baylor welcomes students from all 50 states and more than 80 countries to study a broad range of degrees among its 12 nationally recognized academic divisions.

ABOUT THE BAYLOR UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES

The Baylor University Libraries support excellence in teaching and learning, enhance research and discovery, and foster scholarship and success. Through its Central Libraries and special collections – Armstrong Browning Library, W.R. Poage Legislative Library and The Texas Collection – the Libraries serve as academic life centers that provide scholarly resources and technological innovation for the Baylor community and beyond.